I had not intended to write anything more for the blog before next month, but thanks to the Prime Minister I find I have more time on my hands than I had expected. This Christmas will be like no other. By coincidence, I read recently Jan’s father’s letters to his parents from India and Burma. On 31 December 1944 he described the celebrations of his army unit in Comilla, India (now Bangladesh), in the tropical lowlands, so a white Christmas was impossible. The party was held in the basha (a thatched bamboo hut) which served as the enlisted men’s’ mess. The men had turned this, as far as they could, into a pub called the Bullock Inn to resemble home. Here was a little bit of England in a corner of the Empire. Ron Waddams’ description of a 1944 Christmas describes celebrations which were very different to those he was accustomed to at home in London.

Ron's photos from Comilla and Imphal, modern Bangladesh. The basha is pictured in the two photos top left

“We started our celebrations last evening [Christmas Eve] with a little drinking party in our new recreation hut. This hut we had previously decorated and it looked most cheery with bunches of leaves to replace holly, a large painted Christmas tree with pin-up girls stuck all over it, around the walls were sketches of more beautiful girls, and some cartoons of the boys, the one of me is very good so I intend to send it to you with the Programme, and in one corner of the hut we have a very interesting bar fixed up. So the stage was well set for the evenings [sic] fun … [W]e started of [sic] with a darts competition. In this I managed to reach the semi finals, but then I was knocked out. Boiled sweets were handed round and we each had a bar of Cadbury’s chocolate, just like being at a kid’s party. The rest of the evening was whiled away with a few rums, and as the drinks flowed among the boys, so did the chattering grow and the jokes became more savoury. Indeed, the atmosphere soon became thick and blue, like that of our worthy hostels in England, and when bawdy song broke over the gathering the likeness was even more true. The boys made me sing: ‘Popeye the Sailor’.

Cartoon of Ron drawn for Christmas 1944

On Christmas morning in accord with old traditions the sergeants came round to wake us up, and brought us all coffee and rum to help clear the cob webs away. The day was gloriously sunny, and nothing like the cold snowy day you had in London which I have just read about in a newspaper. It was so inviting, that after breakfast I decided to go for an easy stroll, partly to enjoy beautiful natures and partly to clear my head, which wasn’t exactly thick but a trifle muzzy. I went down a footpath all closed in with leafy bushes and overlaying palms. This eventually brought me out onto a river bank, where on a strip of grass I had a rest. Rivers always seem so soothing to me. I remember I used to go down to watch the Thames at lunch time when I was working in the Strand. This water was just as muddy as the old Thames but not half as wide. A few native dhows passed me by. These were propelled by long bamboo poles used like punt poles, and were very flimsy affairs, in which the scruffy occupants seemed to be continually baling water out. The land on each side of the river is naturally fertile, though at the time it looked pretty bare as the rice has been harvested, and now the farmers are beginning to flood the land once more in preparation for the next crop. Next they will plough up the mud with their wooden ploughs drawn by two bullocks, and then plant out the rice seedlings which look like blades of grass six or nine inches high. After a little meditation on the humorous fact of being surrounded by such country on Christmas Day, I returned to camp for dinner. This was remarkably lavish, considering our distance from civilization. First course was cream tomato soup, followed by roast goose (a bit tough) and suitable vegetables; then came a really good Christmas pud with stodgy mince pie floating in cream; there was also beer, but I did not fancy this with dinner so I had tea. After a weighty consumption there was nothing left that I could do, but return to my bed, and as is the habit of gentlemen at these times, to slumber. I regrettably had no appetite at tea time, and there was fruit salad, trifles, and cake, but I made the best of this misfortune almost to bursting point. The evening’s fun passed very similarly to the previous one, though instead of darts we had ‘Housey-housey’, and a quiz contest, while the supporting surroundings were remarkably the same. I went to bed early at midnight, while I believe some of the lads were up till after four.”

Note: Housey-housey was a popular children’s fairground game. It was essentially the same as bingo, but without bingo’s gambling for money.

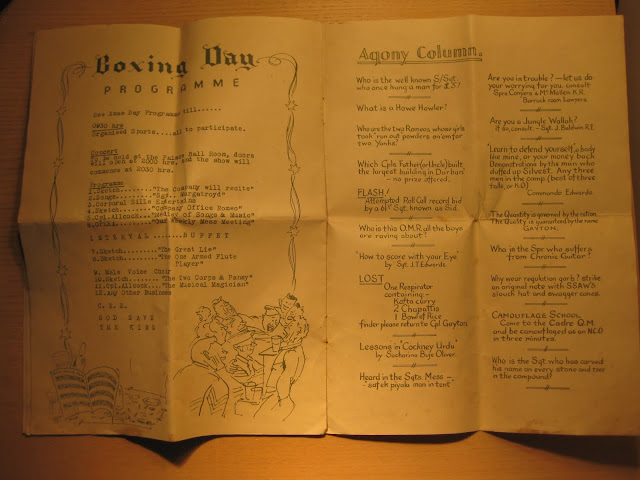

The lavish Christmas 1944 fare was typical of catering for celebratory events far from home, as demonstrated by the 1943 Christmas Programme, designed and printed by Ron’s unit, the 61 Indian Reproduction Group R. E. I. E. (Royal Engineers Indian Engineers: Ron and his English colleagues were soldiers of the Royal Engineers, but they were worked with Indian troops). Their mission was to print maps to plan the Burma campaign, so they had the skills and equipment to print programmes for Group events. In 1943 they were in Dehra Dun, in the foothills of the Himalayas, the headquarters of the Indian Survey.

|

| The Christmas 1943 Programme |

Reading Ron’s letters, I have learned that while an orange or lemon was an almost unobtainable luxury in the headquarters of the Empire, food was abundant in India for soldiers and the expatriate British. When Ron reported to his parents what he had eaten on a visit to a Chinese restaurant (there seem to have been Chinese restaurants everywhere in 1940s India) he would often preface his description with “this will make your mouths water”. One letter includes a description of a mango, a fruit previously unknown to him and his parents. And, extraordinary as it may seem, he was able to send his parents regular parcels of foodstuffs or textiles (also scarce in England but plentiful in India). Attached to one letter are two small swatches of cotton prints sent home so that his mother and sister could make summer dresses.

We had planned to share our Christmas turkey, open gifts and play our traditional games, with two of our three sons in our home. Now, all that will happen, as far as possible, by Zoom. Ron’s equivalent of Zoom was a much anticipated weekly exchange of letters with his parents. News of the Waddams Christmas in London reached him around 21 January 1945.

Let’s hope our festivities can be as jolly as those of Comilla 1944, but perhaps without the pin-ups.