At the end of January, Jan, David and I accompanied John to Berlin, where on his birthday on 2 February, he was to undergo the defense of his PhD dissertation at the Free University of Berlin. More of that later.

While John prepared in his hotel room, Jan, David and I did a little sightseeing. Because the university is in Dahlem, part of the old American zone, we stayed at our usual hotel in the suburb of Lichterfelde Ost, which was convenient for transport links and restaurants and shops. Transport was rather more tricky than usual because of strikes and the closure of a large part of the S Bahn line through the centre of Berlin, so David suggested a short ride south to the station at Lichterfelde Sud and a walk to Teltow at the end of the S Bahn line. As we crossed the boundary of Lichterfelde, the southern extent of Berlin, we entered Teltow in the municipal district of Potsdam.

|

| Teltow's avenue of cherry trees |

Four decades earlier, we could not have strolled into Teltow, for this was the dividing line between the GDR and West Berlin. Today the line of the wall is marked by an avenue of cherry trees planted in 1990 by the Japanese broadcaster TV-Asahi. We followed the long rows of trees to the Teltowkanal and a pleasant canal-side path through the woods that line the waterway – 40 years ago the area was stripped of vegetation and lined by fencing and watchtowers, since the other side of the canal was Lichterfelde and West Berlin.

After walking for a while, we came across two commemorative markers with information about some of those who died trying to cross the canal to the western side. One rather sad case was that of Roland Hoff, who had fled to the East to escape a drunk-driving charge, and then found himself confined there by the newly erected barriers. He protested about the closure of the border and was dismissed from his work for ‘absenteeism’ and charged with ‘inciting slander against the state.’ Roland decided not to attend court for his hearing, but rather packed his belongings (they must have been very few) and sent them by mail to his mother in Hanover. Then he mingled unobserved with workers carrying out maintenance on the canal. He jumped into the water and began swimming to the West Berlin side, but four border guards shot him. His mother was not told of his death. To guard against attempts like Roland’s to escape across the canal, the East German authorities took some care to ensure only trusty types were allowed to live in Teltow. They slipped up in Roland’s case.

|

| Breite Strasse, Teltow |

Teltow was was first mentioned in a deed dated 1265, but it must have been founded earlier because its church of St Andrew dates to the 12th century (although the present church was built in 1812). Lyonel Feininger depicted the church in Teltow II, painted in 1918. Almost all the other buildings in central Teltow were demolished in the 1960s and the town ‘redeveloped’. Still, there’s a reasonably pleasant central, mostly traffic-free, area which conveys some flavour (I imagine) of the old Teltow, much better than do the 1960s apartment blocks and shopping area beyond where the traffic roars constantly by. Nevertheless, the town hall has a tourist office. I think we were probably the only tourists to visit it that day, probably all week. There we discovered that the culinary delicacy of Teltow and its region is a prized variety of turnip. Perhaps poor Roland Hoff was able to enjoy some before border guards brought his life to a premature end.

|

| The church of St Andrew, Teltow |

Our other visit during this trip was to the Berlinische Galerie Museum für Moderne Kunst, a modern art gallery in a converted industrial building. The permanent collection surveys the art scene in Berlin from the late 19th-century on. The art simultaneously tells the story of the rise of Berlin from sleepy provincial town to national capital.

|

| Max Liebermann's villa at Wansee |

The first works in the gallery are showy, traditional pieces designed to please a regional potentate. One of the first pieces to signal a new era of experimentation is a self-portrait by Max Liebermann (1847-1935). At the turn of the century Liebermann was the leading figure in the Berlin Secession, inspired by avant garde experimentation elsewhere in Europe, especially the French Impressionists. One of Jan’s favourite visits during our trips to Berlin has been the Liebermann Villa, on the shores of Lake Wansee to the south of the city. Liebermann and Alfed Lichtwark, director of the Hamburger Kunsthalle, designed the villa’s garden, which Liebermann lovingly portrayed in many paintings. The villa, much changed after it was seized by the Nazis, has been restored to something close to its condition in Liebermann’s days, as has the garden.

|

| Liebermann's self-portrait |

As one browses the collection, one is reminded that the current borders of Europe, which politicians encourage us to consider inalienable and immutable, and to be used to keep others firmly out, are really no such thing. Theo von Brockhusen (1882-1919), a fellow member of the Berlin Secession, was, we are told, born in German Marggrabowa, now Olecko in Poland. Von Brockhusen’s Beach with Bathing Machines, 1909, clearly documents the influence of French Impressionism, and particularly, I think, of Van Gogh.

|

| Von Brockhusen, Beach with Bathing Machines |

Eugen Spiro (1874-1972) reflected another new European style, Art Nouveau, in his work. The model in his portrait The Dancer Baladine Klossowska (Merline), 1901 is Spiro’s sister, herself a painter of the Berlin avant garde, who married the painter and art historian Erich Klosskowski. Spiro’s life again reminds us of the vagaries and tragedies of European history. He was born in Breslau, in Silesia, now Polish Wrocław, a town which has ‘belonged’ to Poland, Bohemia, Hungary, Austria, Prussia and Germany at various times. Like many a Jewish artist of the first half of the 20th century, Spiro ended his life in New York.

|

| Spiro's portrait of his sister Baladine |

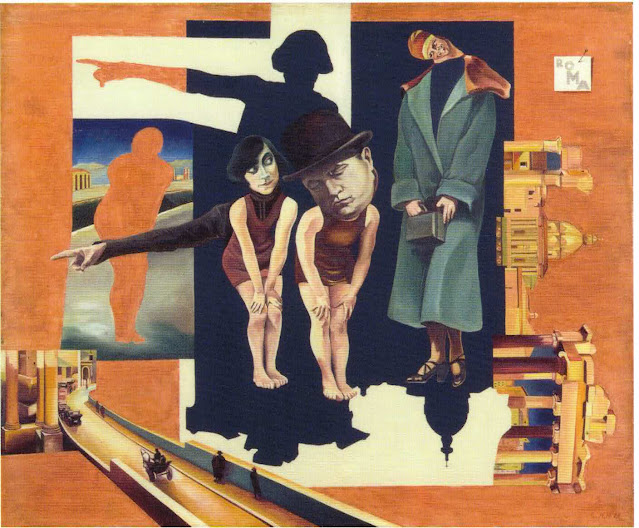

Hannah Höch (1889-1978) was a Dadaist, whose work was much concerned with gender identity, and who liked to poke fun at conservative Weimar society. Roma, 1925, shows us a playful, yet acerbic, personality who enjoyed provoking those she disagreed with. Her art was a natural target for censorship under Nazi rule as Entartete Kunst (‘degenerate art’). Although other members of the Berlin Dada group left Germany, Höch stayed, living quietly in a remote Berlin suburb where she continued working until her death.

|

| Hannah Höch, Roma |

Otto Dix (1891-1969) was another member of the Berlin Secession, famous particularly for his fiercely anti-war images based on his experiences in the German army (he volunteered for service and was awarded the Iron Cross second class). Like Hoch’s Dada works, Dix’s depictions of war were exhibited by the Nazis in Munich in 1937 as Entartete Kunst. Dix, however, was also a portraitist and The Poet Iwar von Lücken, 1926, is one of several portraits of this avant garde poet who lived in severely straitened circumstances. Dix depicts him as a lanky, undernourished man living in a garret that would have served well as a stage design for La Bohème. Oskar Kokoschka also painted several portraits of von Lücken (1874-1935), but the audience for his work was tiny and, apparently he published only one edition of poems (in 1928), of which only two copies remain.

|

| Dix's portrait of Iwar von Lücken |

Georg Schrimpf (1889-1938) was a self-taught artist and, like Dix, a member of the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement. His Two Girls at a Window, 1928, is a charming image sandwiched between the horrors of two world wars. Schrimpf, who was born in Munich, became a professor at the Royal School of Art in Berlin but was fired in 1937 for having been a member of a socialist organization, and public exhibitions of his work were prohibited.

|

| Schrimpf, Two Girls at a Window |

One of the ironies of the avant garde, of course, is that sooner or later it becomes a rear guard, as Felix Nussbaum’s The Folly Square, 1931, suggests. Nussbaum (1904–1944), a surrealist, depicts a group of art students rebelling against the strictures of their elders and betters who, once innovators now uphold out-of-date traditions. Max Liebermann himself is shown on the roof of his house near the Brandenburg Gate painting a self-portrait held by Victoria, goddess of victory (from the victory column to the right). Felix and his wife, as well as his parents and several other family members were murdered at Auschwitz.

|

| Nussbaum The Folly Square |

Berlin’s history is, of course, ever present wherever you go in the city. As a visual overview the Berlinische Galerie is a s good an overview as you can get, and unlike most of the landmarks and tourist sites, it is a testament to human creativity, dissent, a refusal to conform and the questioning of what others tell us is the norm and good for us. The visitor also notices that many of the German artists on show were born in places that are no longer in Germany, and many died elsewhere, driven by Nazi dictatorship to take refuge in other countries, while others less fortunate or who for some reason did not flee died for their art or beliefs.

A panoramic photo of Potsdamer Platz after the enf of the war converys powerfully the enormous damage the city endured, yet still people are seen going about their lives.

|

| Potsdamer Platz (detail) |

To return to John’s exam on the afternoon of Friday 2 February, he gave a 30-minute presentation of his dissertation to five professors who then grilled him (grilled is the word) for almost an hour. We were then asked to leave the room so that the professors could confer. When we were asked back in, we discovered that our son now has a PhD and were all poured a glass of sparkling wine to relieve the tension.

.jpg)

.jpg)