In the Easter vacation

of 1971, instead of heading home to Ipswich, I caught a bus from Cambridge to

Scotland. My destination was the University of St Andrews, where I was to take

a crash course in Quechua at the Centre for Latin American Linguistic Studies,

founded by Douglas Gifford in 1969. Douglas was a large man with an even larger

character. He was born in Buenos Aires (his middle name was Juan) and initially

specialized in Medieval Spanish. He was also a keen musician and conductor of a

choir. I stayed in Douglas’ book-lined house and spent my days drilling myself

in Quechua vocabulary, grammar and pronunciation. All I can now recall are two

phrases: Qata ukhupi kuru kashan (“there’s a worm in my blanket”), a

pronunciation exercise to learn the different consonant forms (glottal stop,

aspirated and unaspirated), and marido ukhupi (“where is your husband”),

which was useful as will soon be apparent.

The reason for my

course in the indigenous language of Peru was that I had been enlisted as the

|

| General Velasco (saluting) with Salvador Allende of Chile (left) |

interpreter for two geographers who were to study the agrarian reform programme

of the revolutionary military government of Juan Velasco Alvarado in the

Urubamba Valley and the Pampa de Anta in the south of the country. We

accidentally met Velasco and his cabinet during the celebrations of the 150th

anniversary of independence in Lima. We joined a long line of locals who we thought

were queueing to see the presidential palace. In fact, they were waiting their

turn to be greeted by Velasco and his cabinet. The generals who ruled Peru were

clearly surprised to meet three Englishmen, especially my companions who were

preternaturally tall by Peruvian standards.

Velasco’s government

lasted from 1968 to 1975. Our visit to Peru was too brief to understand in any

detail the country’s politics. We did learn, the day after we met Velasco, that

there was opposition. We were in a bookshop in central Lima buying a Quechua

dictionary. We heard a good deal of shouting and almost immediately a water

canon sent a bolt of water almost directly into the bookshop. Fortunately, it

missed us and my dictionary, but a good part of the stock was destroyed.

Shortly afterwards, when we reached Cuzco, the ancient capital, we learned that

the university students were on strike. As we toured the sights of central

Cuzco, we noticed trucks full of soldiers in the streets around the Plaza de Armas, the main

square. The next day the local paper informed us that the army had attacked the

university campus with tanks and gunfire from planes.

|

| Cuzco: the Plaza de Armas and cathedral in the centre |

Mexico and Peru have

some things in common. They were both the location of important civilizations

long before the Spanish arrived with permission from the Pope to conquer and

evangelize. The Aztec, Tarascan, Mayan and other ancient civilizations left

marks on Mexican society that are still evident today. In Peru a single indigenous

group dominated in the 16th century, the Incas, whose language was

Quechua. While ancient Mexican civilizations were based on the cultivation of

maize, Andean cultures relied on the potato, of which they had many varieties.

Another difference between ancient Mexico and Peru was that, unlike the Mexico,

where there we

|

| An alpaca herd |

no domestic animals larger than a turkey, Peruvians had

domesticated large animals (camelids such as llamas, alpacas and vicuñas) that

could be used as beasts of burden or sources of wool (Mexicans had cotton but

no wool). The indigenous element of Peruvian society is much more striking today

than in Mexico.

|

| Indigenous women |

People in indigenous clothing, especially women wearing top or

bowler hats and voluminous skirts, are much more visible and Quechua has

survived more vigorously than Aztec Náhuatl.

We were based in Calca

not far from Cuzco in southern Peru, initially on a mission farm run by a

couple from Northern Ireland, and then a house that the mission owned in town. The

setting was quite stunning: the river, lined by eucalyptus tress for many

stretches, runs thourh a valley surrounded by snow-tipped mountains. We

wandered up and down the valley interviewing farm workers and landowners about

the reform programme. I would introduce myself in Quechua and then, hoping that

my interviewees were bilingual, would ask questions in Spanish.

|

| A bowl of chicha |

Workers in the

fields would invariably offer us a drink of chicha, an alcoholic

beverage made by chewing maize kernels and spitting them out to ferment. The

two geographers found chicha quite repellent, so I spent many days

drinking cup after cup of chicha as we progressed along the valley until

I could hold no more. If we came upon the lady of the house, my phrase marido

ukhupi would come in handy.

Our interviewees

included the young mayor of a village whose trade was mending ploughs. His adobe

home was decorated with posters of Che Guevara, Marx and Lenin. He showed us a

detailed census of his village carried out by students from the University of

Cuzco. Later we met the local landowner, who lived in a substantial house with

his unmarried daughter. They had a rather elegant grand piano in their living

room: how it made its way far into the Andes I had no idea. The landowner,

naturally, described the mayor and his supporters as lazy thieves.

Although Quechua was

the native tongue of the indigenous population, the official language of Peru

was Spanish. I had learned in our first days in Lima that Peruvians of the

upper classes would not deign to speak Quechua, and would congratulate me

effusively on my elegant Castilian. Not “Spanish”, but Castilian, the prestige dialect of the

Spanish motherland. Language, ethnicity and class were inseparable, as an

incident we witnessed on the Pampa de Anta demonstrated.

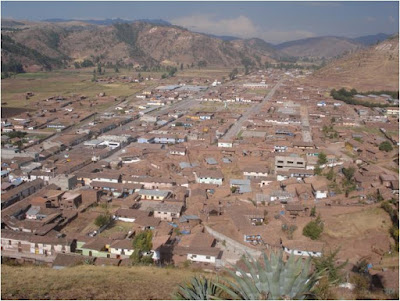

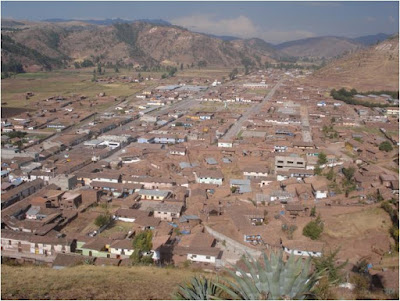

|

| A general view of Anta |

A pampa is a

treeless plain, in the case of Anta high up in the Andes. We travelled there by

local bus to visit the administrator in charge of the local agrarian reform

programme. As we waited outside his office with a large number of indigenous

men, a smartly-dressed fair-skinned woman with an equally well-dressed young

daughter entered and made herself known to a secretary. She was instantly

ushered into the administrator’s office, leaving the rest of us to wait until

she had finished her business. I assumed that she was a landowner, certainly

not a peasant. In any case, her ethnicity and Spanish tongue guaranteed that

she did not need to wait like the rest of us.

The Incas, who had

built cities, roads, storehouses and a powerful Andean empire until Francisco

Pizarro led his group of Spanish adventurers to conquer Peru 1528-1532. The

Inca heritage attracts large numbers of tourists. Visitors to the ancient Inca

capital Cuzco cannot fail to notice that the structures that the Spanish

conquerors erected on the ruins of the city sit atop massive Inca stone walls,

a fitting metaphor for the conquest. Inca masons were highly skilled.

|

| Inca stonework in Cuzco |

They cut

massive blocks of stone so precisely that one cannot insert even a thin blade

between them. The famous “lost city of the Incas”, Machu Picchu exhibits

similarly impressive stonework.

The Quechua people of

the Urubamba worked the fields of the valley floor or the terraces that climbed

the mountainsides with very little technological help. The flat land could be cultivated

with a simple plough drawn by an animal. One day we climbed the terraces of Urubamba

town to a tiny settlement high above the valley floor where the fields seemed

almost vertical.

|

| A chaki taklla |

Here the only feasible implement was the chaki taklla,

a digging stick of the type used four centuries ago by the Incas. In short, the

Quechua laboured hard for very little financial reward. Life was made

tolerable, partly by drinking chicha, and also by chewing the leaves of

the coca tree, which numbed the senses.

While we were in

Calca, the town held its annual fiesta. The square filled with food stalls and

large cauldrons of hot, sweet bean chicha coloured with a livid purple

dye. A good many revellers were quite drunk by the time of the highlight of the

evening, the firework display. The fireworks consisted of a variety of models

such as battleships or tanks on platforms set atop a pole held by one man while

another lit the fuse. The height of the poles was designed to direct the

fireworks over the heads of the crowd. Now, in 1970s Peru I was tall. My

companions, however, were so tall that those in charge of the fireworks could

not have made allowance for their presence. As bolts of fires shot straight at

them they were forced to duck down and miss most of the display.

Drunkenness has deep

cultural roots in Peru. The Incas held public ceremonies in the large main

square of Cuzco and rewarded their subjects with great quantities of chicha.

A curious feature of Inca society was the preservation of dead members of the

ruling group as mummies, who were given their own homes and household staff to

look after them. The mummies presided in silence over the bibulous celebrations

in Cuzco. The Spanish, afraid of the symbolic powers of the mummies, seized

them and sent them to Lima, the new colonial capital. A few years ago, I

listened to a lecture by an American archaeologist who wondered whether the

mummies had survived centuries of colonial rule and modern urban development.

Alas, he failed to find a single mummy.

|

| Sacrificial Inca mummies, not of the royal sort |

After we had finished

our research in the Urubamba valley and on Anta, we decided to visit Bolivia.

|

| A reed village on Lake Titicaca |

Our first stop was Lake Titicaca, which sits astride the Peruvian-Bolivian

border. Tourists go to Titicaca to see the reed boats and villages of houses

constructed of reeds on reed islands. We had intended to cross the border into

Bolivia the next day but, as it happened, president Juan José Torres, like Velasco

Alvarado a left-wing military man, was deposed by another military leader, Hugo

Banzer, supported by the USA and the Brazilian military dictators, and the

borders were closed.

As for General Velasco

Alvarado, his military colleagues deposed him in 1975 and he died quietly in

1977.

No comments:

Post a Comment