Shortly before we left for our visit to friends in Mexico

City and to our son in Bahía de Banderas on the Pacific coast, I read the

obituary of Luis Echeverría Álvarez who was President of Mexico when I first

arrived in the country in the summer of 1972. The governments of Mexico had

agreed an exchange programme: Mexican students would go to the UK to bring back

technical skills and British students would be awarded a stay in Mexico funded

by the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (National Council of Science

and Technology). The three who arrived together on a BOAC flight were

historians: my companions were Alan Knight, who would become Professor of Latin

American History at Oxford and Guy Thompson who had a long career at the

University of Warwick. Reading of Echeverría’s death, I realized that my

connections with Mexico are now half a century old. It seemed a good time to

reflect on those five decades.

Those three months in 1972 were incredibly exciting. I read

about Mexican history in the library of the Colegio de México (the elite

graduate social sciences school of Mexico) and travelled at the expense of the

Mexican taxpayer to visit places that I read about in histories of the Mexican

Revolution of 1910-1921: to Cuautla, where the forces of the peasant leader

Emiliano Zapata once gathered his troops; to San Luis Potosí, the northern city

that gave its name to the manifesto of the first revolutionary leader, a

wealthy, rather mystical northern landowner, Francisco Ignacio Madero, who

actually launched his rebellion from the USA, not from San Luis; to Veracruz,

the Gulf coast port, so often invaded by foreign powers in pursuit of

territorial and political profit; from there Alan Knight and I took a long bus

journey to the port of Tampico in the far north, travelling through tropical land

where the British Pearson company once had its oil fields. I discovered how

hospitable the Mexican people are and made friendships that have lasted for

half a century. I returned in 1974-1975 to carry out research for my doctorate.

I was fascinated by the great metropolis which was Mexico

City, once Tenochtitlan, the city in a lake that was the capital of the Aztecs.

The centre of Tenochtitlan was a great plaza, framed by the palace of the Aztec

ruler, the huey tlatoani (“the man who speaks”) and temples, the

greatest of which was the Templo Mayor (the Great Temple of the Aztecs). When I

was there in 1972 it lay hidden under the colonial structures of the Ciudad de

México, the capital of New Spain as Mexico was known for three centuries of

Spanish rule, but was discovered in 1978 by workmen and is now a visitor

attraction and a museum. During Spanish colonial rule the square was the Plaza

de Armas, where Spaniards mustered if needed to defend the King’s realm or to

calm period fears of a Black slave rebellion. On the site of the palace of

Moctezuma the Spaniards erected what Mexicans now call the Palacio Nacional,

where the President has his offices (and the current incumbent his official

residence). The historic centre soon filled up with palaces and a considerable number

of churches, monasteries and convents, all funded by the rich and powerful who

made their money in trade with Asia and Peru, in silver mining, livestock, or

corruption, the Mexican vice introduced by the Spaniards. In 1972 many of the

religious buildings, expropriated by anticlerical governments of the 19th and

20th centuries, were public institutions: the National Library, the

National Newspaper Library, museums and so on. In modern Mexico, the great

square is known as the Zócalo, which translates as “plinth”, an odd name to

give to the political centre of the country. The reason is that in 1843 Antonio

López de Santa Anna, who frequently but usually briefly occupied the presidency

in the first decades of independent Mexico, had work begun on a grandiose monument

to independence in the square. The project had got as far building a large

plinth when the Americans invaded in 1846, after which Santa Anna’s monument was

forgotten, except in the popular name of the plaza. The plinth, by the way, was

discovered by archaeologists, who usually unearth Aztec remains, in 2017.

Everywhere I travelled in the now enormous metropolis,

Mexico’s turbulent and often sad history was evident. The Metro, recently

constructed for the Olympic Games of 1968, unearthed Aztec remains which were

on view in some stations. In Coyoacán, once a rural town, I saw the mansions of

some of the most important conquistadors, such as Diego de Ordaz and Hernán

Cortés himself, the leader of the Spanish invaders. On the hill of Chapultepec

stands the castle (really a large palace), the residence of Emperor Maxmilian,

the Austrian prince installed by Napoleon III as the second emperor of Mexico from

1864 -1867 (the first, a Mexican royalist, Agustín de Iturbide, wore the crown from

1822-1823). The palace was later the favourite residence of dictator Porfirio

Díaz (1877-1911). At the foot of the hill stands the monument to the Niños

Héroes, cadet soldiers who refused to surrender to the invading

Americans (1846-1848), preferring to jump to their deaths. Their sacrifice is

commemorated every September just before the fiestas patrias that mark

Independence. The latter begin at midnight on 15 September when the President

emerges on the balcony of the Palacio Nacional to give the Grito (the “Yell”

or call to arms against the Spaniards) first made by the priest father Miguel Hidalgo

y Costilla in 1810 on the steps of his church in Dolores Hidalgo. Nobody knows

exactly what he said, but the traditional grito of Viva México!

is brief and to the point.

The city expanded beyond the colonial-era centre in

neighbourhoods known as colonias. Colonia Cuauhtémoc, a short distance

from the centre was a late 19th-century development to the north of one

of the city’s great avenues, the Paseo de la Reforma. Here the well-to-do of

the Porfiriato, the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz, built solid mansions that

have survived earthquakes and political upheavals. The British embassy is in

one of them (actually, it suffered considerable quake damage a few years ago,

but still stands). Roma, and Condesa where I lived, were developments of the

first decades of the 20th century. The expansion of the city picked

up pace after World War II, eventually engulfing formerly independent villages

such as colonial Coyoacán, and, as tram lines developed, further still to the

south as far as San Ángel, an area of charming cobbled streets and expensive

homes combined with still more plazas, olonial churches and monasteries. The

city now sprawls over the valley, engulfing parts of the adjoining state of

Mexico.

In the summer of 1972, I found myself in a Mexico that lived

under the managed democracy of the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI)

that emerged from the years of revolution. This was the Mexico that had

committed itself to universal education, a goal still imperfectly achieved, but

a noble goal nevertheless. The national university (Universidad Nacional

Autónoma de México, UNAM) turned out highly qualified economists, engineers, lawyers,

doctors, archaeologists and so on who staffed the government and provided professional

services on a par, for the wealthy and the middle classes of the cities and

major towns, with more prosperous countries. Rural provision was much inferior,

although graduates were obliged to give a year of social service in the

provinces, and schools and clinics appeared in small towns, but not in many

remote villages and hamlets. I lodged with such a middle-class family (still

dear friends) in Condesa (the land had once belonged to a countess). Nearby the

Jockey Club had established a horse racing track in the 1920s, whose layout can

still be seen in the oval shape of Calle Amsterdam. My first landlady, Consuelo,

was the widow of a businessman engaged in shipping. Her eldest daughter married

an UNAM-trained economist who worked for the Ministry of Public Works, the son

of one of her father’s business friends. After Consuelo’s death her daughter’s

family moved into the house and I lodged with them. The government kept such

families happy by paying a salary top-up “off the payroll” (“fuera de la

nómina”), providing a subsidized ministry shop and enabling them to live

comfortably.

There were similar subsidized shops for some of the more

humble classes run by the Consejo Nacional de Subsistencias Populares

(CONASUPO). CONASUPO’s shops were closed in 1999 to be replaced with a much

smaller number that cater only to communities that live in what the government

considers extreme poverty. The poor’s share of economic prosperity is still

much less than the lifestyle of the middle class: inequality has increased

markedly in my own country, but in Mexico the gap between rich and poor is

staggering. The man who belched fire from his mouth to earn a few pesos in 1972,

the children singing romantic ballads or selling chewing gum on the buses and

metro, or cleaning windscreens at red traffic lights, were not beneficiaries of

the PRI’s “Mexican miracle”. These poor people worked hard and with great

ingenuity to scrape together enough to eat one day at a time. I remember one

day seeing a young man pedalling a bicycle along the Alameda in central Mexico

City. Behind him was a pile of newspapers and seated on the pile was his

partner. As they approached a newspaper kiosk, the boy on the newspaper pile

pulled a bundle from under him and flung it to the newspaper seller. To my

amazement the pair barely wobbled, let alone lost their balance. Slightly

better off perhaps were the members of the “informal economy” who sold fruit-flavoured

water (known as aguas frescas), tacos, tortas (a sort of Mexican

sandwich) and other foods on the street. The contrast with the lives of the

middle-class residents of Condesa, the rather more upscale homes of the

Pedregal de San Ángel, newly-built on an ancient lava field, or the rich and

powerful of Lomas de Chapultepec emphasized the enormous inequalities of 1970s

Mexico, which are still painfully visible today.

Much as these urban dwellers lived precariously, in rural

areas life was more basic still. The homes of all but the well-to-do (if there

were any) were frequently one-or-two-room affairs of adobe. Larger settlements

would usually have a basic school building, although smaller places even in the

21st century sometimes still have schools made of “palos” –

literally “sticks”. Larger villages might also have a one-room clinic run by

the Instituto Mexicano de Seguro Social (IMSS). The more fortunate might have a

parcel of land provided by the agrarian reforms of the post-revolutionary era,

but by the 1970s population growth was fragmenting the holdings, creating a

landless rural population and driving migration to the United States.

The post-war economic growth managed by the PRI regime had

provided families such as the one I lived with an income sufficient to employ

two young maids, to live in a comfortably appointed modern home and to run a

car. True, imported goods were heavily taxed and beyond their reach. While a

similar British family might serve wine at a social gathering, the parties I

attended were lubricated with plentiful rum and tequila. Wine and other foreign

luxuries were for the wealthy, as were restaurants such as Churchills, a

veritable institution which braved every national misfortune except for the

recent pandemic during which it closed its doors for good. But by 1972 the

shine was beginning to wear off the political and economic “miracle” of the

Mexican revolution. There was discontent in rural areas fuelled by poverty and

the rule of corrupt and brutal political bosses. There were rural guerrillas in

the mountains of the state of Guerrero where I studied the 1910 Revolution. In

Mexico City there had been enormous peaceful student demonstrations (later

joined by workers) in 1968 just before the Olympic Games to protest against

restrictions on liberty, official corruption, and the still widespread poverty.

My landlord Alfonso and another friend were present in Plaza of the Three

Cultures and the housing complex of Tlatelolco, famous for its provision of

decent working-class homes, on 2 October 1968, when the regime lost patience.

Soldiers shot many students dead, arrested others, and the fortunate fled to

hiding places in the countryside.

Luis Echeverría, who as Secretario de Gobernación (Interior

Minister) had ordered the massacre, was chosen by the PRI to be elected

President in 1970 (the PRI always won national elections until 2000: the

competition was to be chosen as candidate, not elected). Echeverría struck a

leftist pose, getting politically close (but not so close as to irritate the

USA too much) to Cuba, and associated Mexico with the movement of non-aligned

nations. He promised an “apertura democrática” (democratic opening) but

sent soldiers to the mountains of Guerrero to conduct a dirty war against

dissidents, despatched government-paid thugs called halcones (falcons)

to commit the Corpus Christi massacre on 10 June 1971, and shut down a critical

newspaper, Excélsior. Journalists and other writers were kept onside

with cash subsidies or appointments as ambassadors to desirable countries. The

government controlled paper imports, and consequently could silence excessive

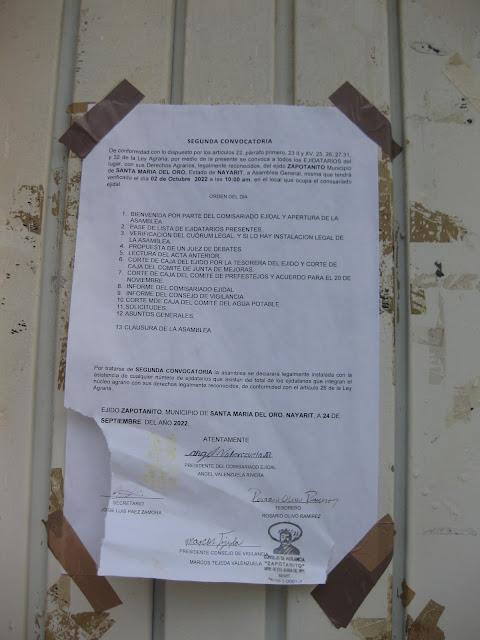

dissent in the press. Echeverría splashed cash with abandon on projects that

took his fancy, such as a fruit canning factory in the village in coastal

Nayarit where he had a vacation home. His six-year period in office ended with

a currency crisis. This rather verbose man, one of whose much-derided phrases

was “No es ni el uno ni el otro, sino todo el contrario” (“it’s neither

one thing nor the other, but quite the opposite”), failed to secure the PRI’s dominance

of Mexican politics in the long run.

In the next two and a half decades the PRI would struggle to

hold power with the firm grasp to which it was accustomed. In 1988 the party

had to resort to post-election rigging of the count to prevent the Partido de

la Revolución Democrática (Party of the Democratic Revolution) of Cuauhtémoc

Cárdenas (son of one of the regime’s most famous presidents) from reaching

power. Finally, the PRI’s candidate for 2000, Luis Donaldo Colosio, was

assassinated four months before the election. As luck would have it, constitutional

provisions prohibited anybody who held a government post less than six months

before the election from being a candidate, which eliminated all the most

powerful alternative candidates. The only possible candidate available, Ernesto

Zedillo, did one remarkable, unheard-of, thing: at the end of his term, he

permitted a free election that the PRI lost.

Many PRI politicians switched to other parties or formed new

ones. One such was Andrés Manual López Obrador (known as AMLO: contemporary

Mexico has a habit of turning public figures into acronyms), from the southern

state of Tabasco, a region known to British readers from Graham Greene’s

evocative novel of the anticlerical 1930s, The Power and the Glory. AMLO,

also known less flatteringly as “el pejelagarto” (a Tabasco reptile with an

extra-large mouth), for his verbosity, joined the PRD and was elected head of

the Federal District, as Mexico City was formally known, in 2000. He ran for

the Presidency in 2006 and vigorously disputed the result when his opponent

Felipe Calderón of the Partido Acción Nacional (National Action Party) was

declared winner. He similarly disputed the elections of 2012, when he was

beaten in the polls by the PRI’s man Enrique Peña Nieto (EPN: as I said,

anybody who is anybody is now an acronym), but then won big with an

unprecedented landslide in 2018 as the head of his own party, MORENA ( and

other acronym for Movimiento de Regeneración Nacional: National Regeneration

Movement).

So, the Mexico I now visit to see my son is the country of

AMLO. This is not the Mexico of 1972. The infrastructure is much more modern.

Multi-lane toll highways now take freight, passengers and private cars to all

the main cities and a good many lesser towns. All the major cities and tourist

areas now have airports. 1972 Mexico City already had multi-storey buildings,

but now it has many more skyscrapers. Wealthy Mexicans drive expensive cars,

live in luxurious houses (probably several) and vacation around the world. The

middle classes now eat in restaurants offering a variety of international

cuisines, even in small provincial towns, and drink imported wines (and some

good ones from the nascent Mexican wine industry). Almost everybody, it seems,

has a mobile phone and communicates by WhatsApp to arrange everything from a

drink in a bar to a business meeting. But the fire eaters, jugglers and trick

unicyclists are still at traffic intersections, as are the children begging for

a few pesos while a parent waits nearby (children receive more sympathy than an

adult) and the children who clean windscreens at red lights. In Bucerías, where

luxury condos line the beach, we saw a family of two adults and three small

girls, the eldest no older than six, loaded with merchandise walking to the

beach for a day selling to holidaymakers in the hot sun. We also saw a boy and

a girl, no more than ten or eleven years old, with no adult present, trudging

along the beach at Bucerías laden with textiles and bags for sale. These

children and their parents still toil daily to barely meet their basic needs.

The children’s education suffers and so poverty is reinforced.

I have not had the close-up view of contemporary Mexico that

I had in 1972 and 1974-1976, but AMLO, who is regularly characterized in the

British press (in so far as our press refers to him at all) as a leftist,

strikes me as no such thing, but rather a politician made in the mould of old-style

authoritarian PRI politicians. Not so much the suavely corrupt EPN, but the

rough tough, often gun toting politicos of old. However, there is one

difference. While an Echeverría might have kidded himself that the people

adored him and his grandiose projects that came to very little, there was, in

truth, no great enthusiasm for his government. Things are different under

AMLO: those who believe with fervour see

a plan to transform Mexico into a much more prosperous country standing tall in

the world; semi-believers credit him with some good policies but dislike his

authoritarian manner; others (including, as far as I can tell, the better-off

middle class) loathe him as an authoritarian disaster who is taking the country

in the wrong direction. AMLO tends to talk in quasi- mystical terms (one is

tempted to say pseudo-mystical). For example, during the pandemic he told

Mexicans that they would be all right because of their country’s deep cultural

resources and produced assorted amulets and charms that he carries to ward off

disease and other maladies. Nevertheless, whatever one might think of AMLO, he

has undoubtedly succeeded in selling a vision of a more promising, even

glorious future for Mexico to win enough votes to control almost all levers of

power. The overarching framework of the vision is the Fourth Transformation

(acronymed, of course, as the 4T). In

AMLO’s view (it can hardly be called an analysis, since it would fall apart if

tested against what actually happened in the past), Mexico has undergone four

transformations which constitute triumphant moments in Mexican history:

Independence from Spain in 1821; the Liberal Reforma of the 1860s (led

by one of AMLO’s great heroes, President Benito Juárez); the Revolution of

1910-1921 (started by another hero, Madero); and AMLO’s own promised

transformation.

A theme in all four transformations, in AMLO’s account of

history, is independence. He expresses Mexico’s independence in a number of

ways. Like Echeverría, he makes a point of offering support to Cuba, to which

AMLO adds Nicaragua and Venezuela. Unlike Echeverría, however, AMLO seems

uninterested in overseas travel and the international stage. Apart from one

visit to the White House, he tends to despatch Marcelo Ebrard, his foreign

minister, to international engagements. However, the policy that most notably stems

from ALMO’s pursuit of independence relates to petroleum. Petroleum has been

drilled in Mexico from at least the early 20th century, and in 1938

President Lázaro Cárdenas nationalized the industry in the teeth of opposition

from the USA and the UK. But it was in the 1970s that large reserves were found

off the Gulf Coast. PRI politicians believed that they ruled a country that

would become a member of the club of rich oil nations, but things did not quite

turn out that way. For example, Mexico exports crude oil to the USA but then

imports gasoline because it lacks sufficient refining capacity. One of AMLO’s

first acts was to commission a new refinery, Dos Bocas, in his home state of

Tabasco. On the meagre evidence of my conversations, this element of AMLO’s

policy is popular with Mexicans who are not otherwise devotees of the

President. It taps into deep feelings of independence from foreign powers who

have so often bullied Mexico in the past.

To an outsider, this large bet on a technology whose

medium-to-long-term future looks uncertain, to say the least, if other

countries seriously pursue decarbonization, does not entirely make sense. But

to many Mexicans, for whom oil is the very symbol of independence for a country

much pushed around in its 200 years as an independent nation, energy

independence is a very alluring prospect. The trucks of PEMEX, the state-owned

oil company, carry the slogan “por el rescate de la soberanía” (rescuing

sovereignty).

Moreover, a future based on oil seems to be pretty much the

entire energy policy of AMLO’s government. I asked a friend in Mexico City why

I saw no electric cars here: simple, he replied, no charging points. He added

that the new Tren Maya (see below) will run on diesel engines, not electric,

and that construction has destroyed large swathes of virgin forest. One

loyalist whom I asked about the apparent lack of interest in renewable energy

assured me that I was mistaken and mentioned five areas that are the focus of

renewables, such a geothermal. I was not convinced of his argument: after all,

AMLO has prevented renewable energy companies from entering the electricity

market in order to protect the Comisión Federal de la Electricidad (Federal

Electricity Commission) from competition. In essence, a regime for which

petroleum is the very expression of Mexican independence does not really seem

to think the country needs anything else.

In some respects, AMLO’s attitude to the private sector

bears comparison with that of Echeverría, who had particularly frosty relations

with big business, most notably with the wealthy industrialists of Monterrey in

northern Mexico. While some of Echeverría’s hostility was as much rhetorical as

practical, AMLO is instinctively distrustful of the business sector. Soon after

he came into office, he cancelled the construction of a new, half-finished,

international airport, and incurred a compensation bill of some US$93 billion,

perhaps more. The former airport is now to become an ecological park, and a new

airport, converted from a Mexican air force base by the army, has been opened

to supplement the current airport in Mexico City.

This brings us to the role of the army in AMLO’s Mexico. An

important element of AMLO’s appeal in 2018 was his promise to tackle the

violence of organized crime. His policy was “abrazos no balazos”:

embrace the criminals rather than shoot them. His argument was that, if poor

young Mexicans were given alternatives to organized crime, they would prefer a

life of honest labour. He also disbanded the Federal Police and merged them

with elements of the military to form the National Guard, which patrols the

streets and is supposed to tackle organized crime. More recently, he has

brought all police forces under the control of the Ministry of National Defence

and ordered the army to secure the streets of the nation. He recently divided

the three main opposition parties by proposing a law that authorized the army

to provide internal security for the next six years. AMLO’s opponents argue

that this is unconstitutional, but the President shows no interest in

constitutional or other provisions that might constrain him.

The results of the militarization of policing and the direct

involvement of an army not trained to police a civilian population are not

encouraging. Violent crime has not decreased. Rather, according to published

statistics it has increased. A friend from a small town a short drive out of

Mexico City told me that, while there is no violent crime where he

lives, it is common knowledge that local businesses pay extorsion levies to

criminals, many of whom are known to live from such rackets. When we visited

the dog hotel in the Pitillal district of Puerto Vallarta where Chris had

lodged his dog Winston while we were in Bucerías (the apartment owner does not

permit pets), I spotted a sign on a beer shop across the street. It read: “Vigilant

neighbours united against crime. If we capture a thief, we will beat the s**t

out of him.” The British Foreign Office writes the following concerning the

state of Guerrero where I travelled as a young student (my emphasis):

The interior of the state is

dangerous. State security forces have scant presence. Control is often in

the hands of organised crime groups and local ‘self-defence’ organisations.

Foreigners’ presence in rural Guerrero is likely to be regarded with high

levels of suspicion by omnipresent organised crime and local self-defence

groups, and the possibility of misunderstanding and ensuing violence is high.

An archaeologist friend who has worked in Guerrero for

decades, told me that he only dares go there now with a local friend (even to

the state capital), since any outsider is viewed with suspicion and is

therefore vulnerable. Guerrero is an extreme case, but it is not unique. The

British government’s verdict on Michoacán is similar: “some areas are totally

lacking state control and do not have a security presence.” A friend in

Michoacán tells me that the west of the state and adjoining areas of Jalisco

are now known as “the corridor of death”.

No president could solve the problems of Guerrero, or of

other parts of the country plagued with crime, in a six-year term. Moreover, Mexico’s

government is not solely responsible for the increase in organized crime. The

consumption of drugs in the USA has funded the growth of crime south of the

border, and lax American gun laws have facilitated the illegal export to Mexico

of powerful weapons that are illegal under Mexican law. The American love

affair with automatic weapons is responsible for the deaths of many innocent

Americans, but equally for the murder of America’s neighbours. However, there

is little evidence to suggest that AMLO’s handing of a security role to the

army, combined with “abrazos no balazos”, is improving matters.

AMLO has been remarkably indifferent to one of the most

appalling aspects of violent crime: violence against women, and in particular

the murder of women. Mexico has even coined the Spanish-language term now

widely used for this form of gender violence (feminicidio). Violence

against women is widespread, rarely investigated by the police, and in most

cases a crime that men can commit with impunity. Moreover, this particular

violent crime cannot be attributed to the existence of powerfully armed

organized crime groups. This is predominantly a crime committed by individual

men for individual motives. AMLO has dismissed demonstrations against feminicidio

as politically motivated by his “neoliberal” enemies. Since the government

tends to pay attention to issues only if AMLO decrees them worthy of government

action, gender violence is more or less ignored. Such violence existed before

AMLO took office, and occurred in the Mexico I knew 50 years ago, but the scale

of the crime has increased, facilitated by official inaction.

Moreover, the role of the army has been expanded beyond policing.

The military is being turned into a business enterprise that will manage projects

close to the President’s heart. The army has built the new airport (Aeropuerto

Internacional Felipe Ángeles), which a friend reports to be very well built and

organized but with very few people (because few airlines want to fly passengers

to an airport a long way north of Mexico City with poor transport links to the

capital). The army is also building the Tren Maya, a railway that will start at

Palenque, one of the great ancient Mayan cities, passing through the

president’s home state, Tabasco, and then running through cities and

archaeological sites in Campeche, Yucatán and Quintana Roo. Another train line

is planned to cross the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, linking the ports of Salina

Cruz on the Pacific Coast and Coatzacoalcos on the Gulf. AMLO’s stated goal

here is to replace the Panama Canal as the preferred transhipment route between

China and Europe.

This reliance on the army is a huge departure from the norm.

There was a time when historians argued that post-revolutionary Mexico had

found a novel formula to keep the military out of politics, unlike many other

Latin American countries that suffered brutal military dictatorships. In fact,

the army was more important for political control of the country than

historians thought: the 1968 suppression of protests and in the 1970s the dirty

war in Guerrero and elsewhere proved that. But formally to hand the army

responsibility for civil law and order and for large business enterprises is

another matter. What will happen if the generals rather like their lucrative

roles and dislike giving them up?

A recent article in El Universal (11 September 2022) is

not encouraging. Since the formation of the National Guard in March 2019 There

have been 8,656 complaints of extorsion, abuse of authority, assaults and other

matters. The army itself examines all complaints against it. The journalists

were able to examine the records of 1,303 complaints. All were dismissed by

army investigators for lack of sufficient proof. This amounts to impunity on a

large scale: other incidents did not result in complaints since to complain is

a waste of time. However, AMLO seems to be convinced of the absolute honesty of

the military. On 14 February 2022 he said to National Guard officers in

Michoacán: “The most important thing is honesty, integrity, not to be tempted

by corruption, that members of the National Guard can say “I am loyal to Mexico

and am incorruptible and I would rather leave my children in poverty than in

dishonour.” The history of Mexico’s military makes it most unlikely that it

consists entirely of such paragons of virtue.

One wonders, moreover, whether army commanders might quite

like their access to large contracts, and whether it might be unwise or even dangerous

to curtail the army’s activities in future, especially if commanders find them

pleasantly lucrative. This thought is especially troubling in the light of

AMLO’s undermining of the institutions that, since 2000, have helped to ensure

a degree of democracy that might not be perfect, but which is at least an

improvement on the PRI’s controlled political system. AMLO has certainly

attempted to influence the judiciary and to limit the ability of the Instituto

Nacional Electoral (INE: the National Electoral Commission). A friend we met

for lunch in Mexico City arrived at our table excited because she had passed a

table at which Lorenzo Córdova Vianello was eating and had greeted him. Our

friend’s husband added that they consider Córdova a hero for standing up to

AMLO, who they consider a fascist.

AMLO’s hostility to journalists is well-known. I learned

while I was in Mexico City that an international paper which publishes an

edition in Mexico, and which had been critical of AMLO, was told that its

advertising would suffer if it continued to question his policies. The owners

complied. This brought to mind the case of Excélsior, the most

independent paper in the 1970s. In this respect, AMLO is a return to an

authoritarian past, not a harbinger of a bright new future, and his arm

twisting is more direct than the more indirect methods of Echeverría.

Two of AMLO’s great themes, as already mentioned, are “abrazos

y no balazos” and corruption. In AMLO’s world, opportunity for the young

will incentivize them to take on honest work rather than involving themselves

in organized crime. To his credit he has instituted some social programmes for

the young to offer greater opportunity, although a determined lack of

transparency prevents independent evaluation of the results. He also increased

state pensions and required employers to enrol domestic servants in the social

security system to give them access to healthcare. However, he has not

increased the budget of the public health system correspondingly. AMLO insists

that corruption will be defeated by his “republican austerity” and the

unimpeachable honesty of his colleagues in MORENA. Corruption, he argues, was

the sin of previous regimes, not of his. This is seductive rhetoric if one

ignores facts and Mexican history. Only the credulous can really believe it.

But as more than one friend has commented, nobody in his circle dares

contradict AMLO. What he says must be done and must be right.

AMLO is not responsible for Mexico’s many problems and it

would be unreasonable to expect any government to fundamentally transform a

country as large and complex as Mexico in a single six-year term (Mexican

presidents serve only one term), but one would hope to discern in AMLO’s

policies firm directions that point towards sustained and verifiable

improvements during the terms of subsequent presidents. While some positive

steps have been taken, real progress remains in the realm of rhetoric rather

than policy or accomplishment. To some extent, this reflects the rather

depressing politics of our times: think of Donald Trump, Boris Johnson, Viktor

Orbán, Vladimir Putin. Like them AMLO deploys rhetoric that inspires his

followers, however much his detractors may despise him, like them he subverts

norms and restraints on his powers. However, AMLO draws on decades old Mexican

political practices and thinking that a PRI president would have recognized.

However, while superficially a PRI president was, for six years, a king of all

he surveyed, in practice the PRI coalition of interests (unions, peasant

organizations, employers’ confederations) applied some brakes to a president’s

power. AMLO, in contrast, won power with a sweeping majority and recognizes few

if any constraints. He can do much good and can also do immense harm.

AMLO has undermined, but not yet destroyed, Mexico’s

democratic processes that emerged from the defeat of the PRI. He has damaged

constitutional and judicial checks on power. He has enormously expanded the

role of the military in Mexican life, while doing little to address violent

crime. Since he takes all the key decisions, it seems certain that he will

anoint his chosen successor, and since the opposition is weak and divided his

chosen one will probably become president in 2024. If AMLO is then the power

behind the throne, presumably the next government will pursue similar policies.

Despite the increased role of the military, I think it is most unlikely that

the army would seek to seize power directly, but the generals will probably

wield greater influence. If MORENA remains dominant and further undermines

institutions intended to ensure a degree of democracy, Mexico may return to

something resembling the managed democracy of the PRI, but perhaps more authoritarian

and unipersonal. While previous militarized attempts to combat criminal cartels

have failed, AMLO’s policy of non-intervention, or at least minimal

intervention, does not seem to be a viable solution either. In the absence of a

serious attempt to reduce organized crime and its accompanying violence it is

likely that those parts of the national territory that are no longer controlled

by the government will continue to be so, and control of additional regions may

also be lost. And if I were able to come back in another 50 years, I expect

that I would still find children begging at traffic lights and selling tourist

souvenirs on the beaches.

But one thing has not changed, the hospitable and courteous

character of the great majority of Mexicans, a certain formality and insistence

on polite forms of address, which Spaniards tell me they find too servile, but

which I find charming (especially since being older I tend to be the one to

whom formal politesse is directed). Working-class Mexicans are hardworking and

resourceful people. If they are poorly paid and less productive in comparison

with their northern neighbours it is worth remembering that many workers north

of the border are also Mexican. The difference is that, with some exceptions,

businesses in the US are more capitalized and automated than those in Mexico. Many

customers of Mexico’s largest mobile phone company, Telmex, owned by Carlos

Slim Helú, Mexico’s richest man and one of the wealthiest in the world, top up their

phones and resolve customer service problems in retail outlines or in one of

Telmex’s many offices. In other words, it is economic for Mr Slim to employ low

paid Mexican staff rather than to invest in greater automation as his

counterparts in North America and Europe have done. A meagre share of the

changes of the last 50 years has percolated down to the lives of many Mexicans.

By and large they continue to live in a society in which the rich and powerful

bend the law and politics to their benefit.

The ordinary Mexican is still obliged to fall back on hard

work, family, and community resources. For a long time, one strategy has been

to cross the border seeking work and a better life in the USA, but undocumented

Mexicans live in constant fear of some minor misconduct bringing them to the

attention of the authorities. Unwittingly exceeding the speed limit, carelessly

jumping a red light, or annoying a co-worker who informs the authorities of your

irregular immigration status can end in deportation and separation from your

family. One person told us that she had lived in Sacramento for many years,

having three children there, who were all therefore American citizens. She was deported,

initially for a five-year term, later doubled by Mr Trump to ten, leaving her

children with their father. She works and saves all year to pay half her

children’s air fares for a longed-for annual visit (their father pays the other

half). However, in 2021 two bouts of Covid severely reduced her income so the

children have not visited her for more than a year. A man who drove us into

Puerto Vallarta told us that he had crossed the border aged 15 initially to

work in agriculture in California until a friend invited him to work in

Tennessee in road and bridge construction. His children too were born American citizens

and he too decided to leave them in America for a better life. His eldest son

is now a welder in a car factory. The children speak their father’s tongue as their

second language: the welder son learned to write it by copying the Bible in Spanish.

A similar tale, aggravated by the pandemic, was that of a woman who worked in agriculture

in northern California. When she returned to Mexico leaving her children in the

USA, she trained to be a chef of Italian cuisine in a restaurant in Puerto

Vallarta. The pandemic closed the restaurant and when it reopened her employers

cut her salary: she decided that she would be better off driving tourists and fellow

Mexicans around the towns of the Bahía de Banderas. Her children too live in

the USA.

The Americans who voted for Mr Trump because he maliciously denounced

Mexican immigrants as criminals and promised to keep them out of the USA (a

promise as empty as AMLO’s “abrazos no balazos”) are happy to drive on roads

and bridges built by Mexican labour or to eat potatoes graded and cleaned of

stones by hand in northern California by a Mexican mother. However, at the same

time they want those same people sent home and certainly kept well away from Americans

who consume the fruits of Mexican hard work, Americans who are no more law

abiding (perhaps sometimes less so) than the immigrants they despise.