In my young postgrad days, I toured small towns in the state of Guerrero seeking local information about the events of the Mexican Revolution. One such was Mayanalán, reached by a local bus from Iguala, the economic hub of northern Guerrero. The driver deposited me near the medical clinic in the centre of town. There was also a primary school and a small vilIage general store (una tienda de abarrotes). Otherwise, the town consisted of small adobe or breeze block dwellings, generally of two or three rooms. Mayanalán was too small to support the usual billar (a combination billiard hall and beer room, host to many a drunken altercation) that was the social centre for men of larger towns. I had arrived hoping to meet the widow of a local revolutionary general but, unfortunately, she had gone to visit relatives in the neighbouring state of Morelos. Finding that nobody else could tell me anything about the Revolution, I asked if there was a local restaurant. There was not, but I was directed to the home of a lady who could make me a lunch of egg and chips while I waited for the bus back to Iguala. The people of towns like Mayanalán lived from agriculture. Many of them were ejidatarios, members of an ejido, a kind of agricultural quasi-cooperative formed by post-revolutionary governments by expropriating land from large landowners. Mayanalán, I discovered almost half a century later while researching a book about the much earlier history of Guerrero, had been a prehispanic town of sufficient importance that a few subordinate towns owed allegiance to its ruler. In 1535, fourteen years after the defeat of the Aztecs by their Indigenous enemies, assisted opportunistically by Spanish adventurers, the ruler of nearby Oapan sent envoys to request the hand in marriage of Ana Conxochitl, daughter of the ruler of Mayanalán, in marriage. The proposal accepted, the wedding party walked the 140kms or so to Chilapa where the wedding ceremony was conducted by one of the resident friars. Ana must have been a robust young woman.

|

| The kiosko in the plaza of Zapotanito |

|

| The plaza in Zapotanito. Behind the buildings is the Cerro de la Cruz (Hill of the Cross), on top of which stands a small white cross |

While we were in Mexico in October 2022, we were invited to lunch by the family of a friend of our son Chris in their home in Zapotanito, a small town with an ejido in the state of Nayarit. Zaponatito remined me of my visits to towns in Guerrero almost half a century earlier. A paved road off the main highway took us to Zapotanito, but as soon as we reached town the asphalt ran out to be replaced by cobbles or dirt streets. Just like Mayanalán, there was no restaurant or billar here, although there were three or four tiendas de abarrotes, a beer store, and a stationers. In the centre of the town is a small plaza with the obligatory kiosko (bandstand), which was adorned with bunting in the national colours for the national independence festivities held a few weeks earlier. Zapotanito also has a football pitch, a small bull ring, and an assembly hall for the ejido, where the annual general meeting had been held only a few days earlier on 2 October. There is a primary school in the centre and a secondary school on the edge of town. Students who study the last two years of school in a preparatoria, have to travel to Santa María del Oro. A small building a few yards from the plaza bore a faded sign Abasto del pueblo. This was the former slaughter house. On a steep hill above the town stands a small white cross, reached by more steps than we felt like trudging up on a rather hot day. Zapotanito, however, was not an ancient foundation like Mayanalán. Its church was built in 1921, which suggests that it was founded early in the 20th century, perhaps as a direct result of the revolutionary agrarian reform programme.

|

| Zapotanito's football pitch |

|

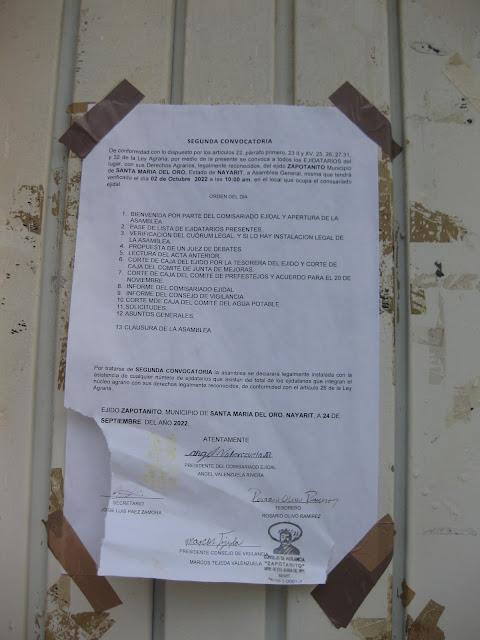

| Agenda for the annual general meeting of the ejido |

The patriarch of the family we visited, Don Dario, 86 years old, was waiting to greet us. Dario is an ejidatario. He grows sugar cane. Dario had a difficult start to his life: his father died when he was very goung and his mother made her living selling gordas (maize dough stuffed with a savoury filing). His home is a single storey structure, painted a cheery blue, built over the years to no predetermined plan as finances had permitted. In the corral to the rear is a cooking area with a wood-burning fire (there is also a gas stove and oven in the kitchen/dining room). An orchard area has a lime tree, a guayaba tree and a chayote (a sort of squash) vine. At the rear, one daughter has built a small home, while another who lives in the USA is building an ample two-storey home close by.

|

| Cooking and serving the pozole |

|

| The pozole is served |

Lunch started with pozole rojo, a long-cooked stew of pork meat and skin and maíz cacahuazintle (which yields large grains, at least double the size of the usual sweetcorn), flavoured with garlic, onion and guajillo chiles. One adds to taste raw onion, lettuce and lime juice. There followed elote (corn on the cob) roasted on the embers of the fire that cooked the pozole. This prompted an explanation by Roberto, Don Dario’s son-in-law, of the terminology of maize: elote, the tender cob of the corn; mazorca, the dried cob, whose grains, cooked with lime, are ground to make the masa (dough) for tortillas and other staples of the Mexican diet. Finally, we were offered a large quantity of empanadas of pineapple, guayaba and cajeta (caramelized milk). We were served first (as guests must always be) and ate with Don Dario, only later joined by two of his daughters and Roberto, while other members of the family ate at the kitchen table. Four generations were present, wandering in at various times from work or from school. All greeted us with a handshake or a kiss.

|

| Lunch with Don Dario |

Dario spent the lunch regaling us with tales of Zapotanito’s history and customs, occasionally supplemented by Roberto. The town had once been the seat of the municipality, and had had its own court and jail, but it lost its municipal preeminence to the larger population of Santa María de Oro. The annual fiesta is an animated affair. Some of the men of the town dress up as women with heavy makeup and tight-fitting shorts, and offer kisses to the other men while bands serenade the populace. The bull ring is the setting for the jaripeo, the riding of bucking bulls, the winner being the rider who stays on longest. The costs, which are considerable, are borne by the mayordomo of the fiesta. The people of Zapotanito seem to enjoy a good time: a dance (free of charge) was scheduled for the Sunday evening after our visit.

|

| A street in Zapotanito |

The other main event of Zapotanito’s year is the procession of the Virgen del Espíritu Santo (Virgin of the Holy Spirit). This dates back to the Cristero war of the 1930s, when the Catholic Church closed its doors and withdrew all sacraments in protest against the anticlerical measures of the federal government. In Nayarit, like much of western Mexico, the faithful rose up in anger at the loss of their masses, weddings, funerals and so on. The people of Zapotanito prudently hid their Virgin in a cave to protect her from the depredations of federal troops. However, a man from nearby Tequepexpan discovered her there and she was carried off to that town’s church. This, naturally enough, caused a conflict between Zapotanito and Tequepexpan, which was eventually settled by a priest who suggested that each town host the Virgin for six months of the year. So, on the appointed date, she is carried some 27kms. on foot (on one occasion during the pandemic in a truck) from one town to the other, accompanied by a crowd of local people and a band, and six months later she ceremonially makes the reverse journey as she has for nearly a century now. Fortunately, the Virgin is a diminutive figure in a wood and glass case, but nevertheless it is quite a feat to carry her a considerable distance over hilly country. The concordat between the two towns is recorded in a signed agreement in the municipal archives and is further recorded on the wall of Zapotanito’s church to the right of the altar. Don Dario told me the story of a man from Los Angeles, California, who lost the use of his left arm. He was advised to seek help from the Virgen del Espíritu Santo. Since there is no hotel in Zapotanito, Don Dario offered the man a room in his house and thus witnessed the miraculous recovery of the man’s use of his arm.

|

| Zapotanito's church. The priest lives in Santa María del Oro and officiates only on Sundays |

The church of Nuestro Señor de Chalma (Our Lord of Chalma - a pilgirmage destination in Malinalco, State of Mexico) in Mayanalán is an older and rather grander building.

|

| The church of Mayanalán |

Of course, 21st century Zapotanito is not the same as 1975 Mayanalán. Some 25% of Zapotanito the population is reported to have completed secondary education and 24% of households has a computer, laptop or tablet. If Don Dario’s family is an example, families are divided between their home town, the USA (many of the younger generation were born there and are citizens), or larger cities such as Tepic or the tourist resort of Puerto Vallarta. Migration to the USA was not at all a new phenomenon in 1975 when I visited Mayanalán, but I don’t remember discussing daughters and granddaughters who had become citizens and permanent residents in the Norte on such a scale. If Don Dario’s family is anything to go by, this is resulting in cultural changes. One of his daughters told me that she encourages her own daughters not to marry at age 14 or 15, which has been the norm, but to establish themselves in a career first. One of her daughters is doing just that in Oregon. Our discussion of the ejido’s crops, or the serving pozole on important occasions was a norm in small-town Mexico in the 1970s just as it is in 21st-century Zapotanito. Don Dario’s house is larger than the dwellings I recall in Mayanalán, but otherwise the domestic space recalls the homes I visited almost half a century ago. And one thing has definitely not changed: the hospitable welcome accorded to a visitor. As Don Dario told us “siempre serán bienvenidos y aquí tendrán su humilde casa” (you will always be welcome and. here you will have your humble home).

|

| Don Dario, two of his daughters, his son-in-law, and the Jacobs family |

No comments:

Post a Comment